In 1945, something remarkable happened. A 67 year old woman opened her eyes and declared “I’m going to divorce my husband”. Which she did. But more importantly, she had also marked a milestone in medical history. The woman’s name was Sofia Maria Schafstadt and she had just regained consciousness from a uraemic coma after 11 hours of treatment on the world’s first dialysis machine. Kidney diseases may have been almost as old as human history itself. Descriptions of kidney disease can be traced to as far back in time as early Rome; although their knowledge of treatment was considerably limited and included the use of hot baths, sweating therapies and even bloodletting.

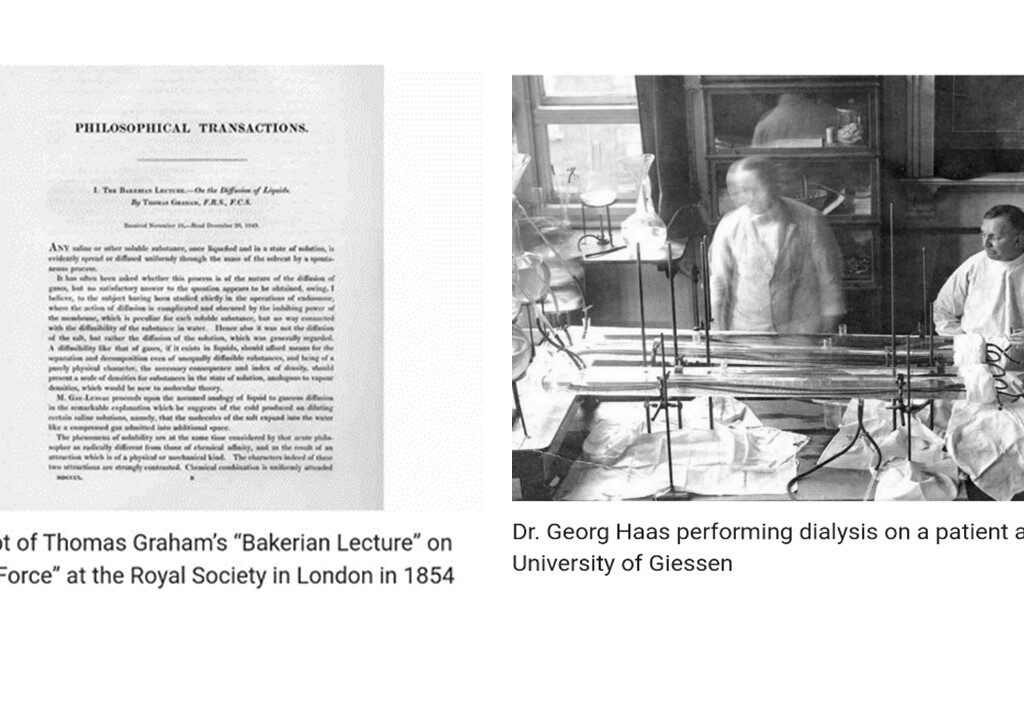

The actual concept of a dialyzer was first conceived in the 1830s by Thomas Graham, a Scottish chemist. In his work Graham explored the possibility of utilizing certain methods used in chemical laboratories for the purpose of separating solutes from their respective solutions, to be used for filtering uraemic substances from the blood of patients with kidney disease. He was referring to the principles of osmosis and the function of semipermeable membranes.

Despite being radically ahead of his time, Graham’s work remained largely confined to being an idea; a mere concept. A practical method of dialysis would not come into effect until 1913, when Leonard Rowntree and John Abel of John Hopkins Hospital came up with a working dialysis system, which they successfully tested on animals.

A German doctor named Georg Haas, performed the first dialysis treatments involving humans. Sadly, none of his subjects survived.

It wasn’t until 1943, that the first medically useful dialyzer would be constructed, by a Dutch doctor named Willem Kolff. Kolff had already begun research on a possible new method to create an artificial kidney while serving as a doctor in the wards of University of Groningen Hospital, Netherlands. Around the same time, the Nazis invaded the Netherlands and Kolff was sent to work in a remote Dutch hospital.

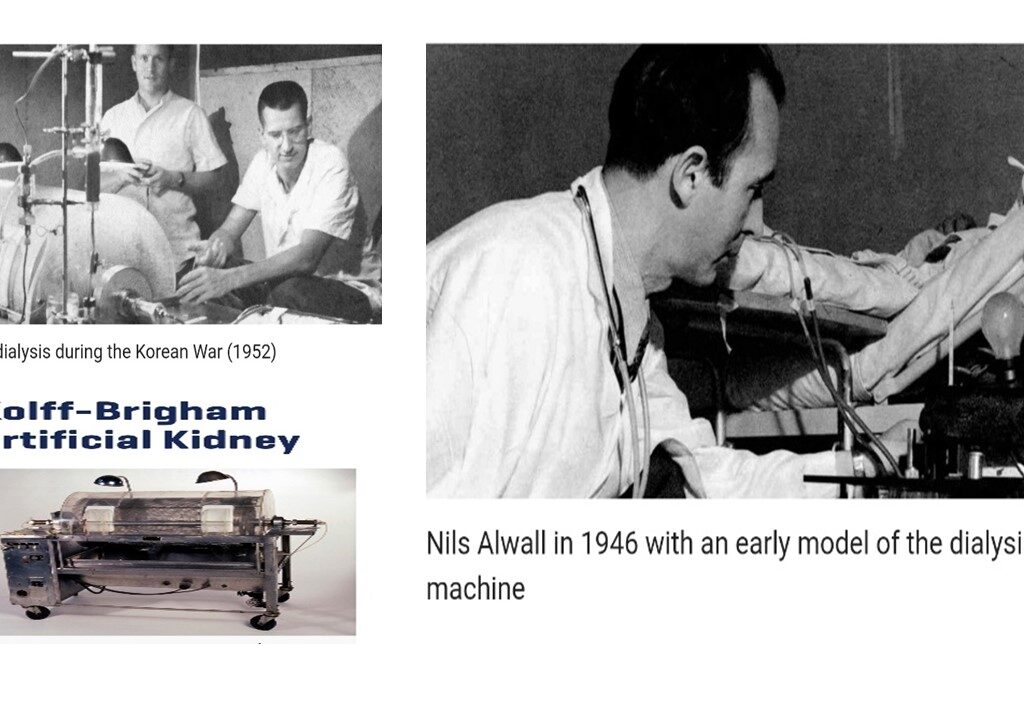

There, Kolff resumed his research and ultimately came up with a functioning dialysis machine, albeit a rather crude one constructed from a washing machine, orange juice cans, sausage skins and other forms of “junk”. Emboldened by his newfound success, he treated 16 patients with acute kidney failure, using his machine over the course of 2 years. All 16 patients died. Then in 1945, Kolff treated his 17th patient, none other than Maria Sofia who recovered from her uraemic coma. She lived for 7 more years before dying of unrelated causes. As for Kolff himself, he never bothered to patent his invention. Instead, he actually distributed copies to hospitals across the world. Some of his machines made their way to Peter Brent Brigham Hospital in Boston, where they underwent a significant technical improvement; giving rise to the Kolff-Brigham artificial kidneys, which first saw practical use during the Korean War.

In 1947, Swedish scientist Nils Alwall published a paper on a new design for a modified dialyzer which would be able to perform the required combination of dialysis and ultrafiltration better than Kolff’s original machine.

Over time, technology improved, modifications were made, and newer more sophisticated versions of dialysis machines were produced. And just as the technology of dialyzers continues to develop, likewise the scientific principles regarding the transport of particles across membranes saw considerable improvements as well, and these in turn were applied specifically for dialysis purposes.

No doubt, we have come quite far since, Kolff’s washing machine and sausage skins. And with each passing day of new discoveries being made, who knows what we will have in store for the future.

Written by Dimantha Bandara

References

1. History of Kidney Disease Treatment, https:// www.sgkpa.org.uk/history-of-the-kidney-disease-treatment

2. The history of dialysis, https://www.freseniusmedicalcare.com/en/media/insights/company-features/the-history-of-dialysis

3. The Oxford Handbook of clinical medicine, 10th edition

Leave A Comment